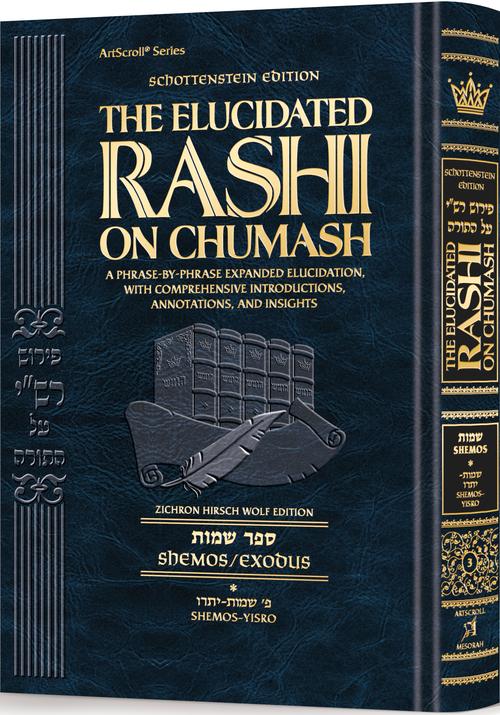

Culled from the Insight section of the recently released Elucidated Rashi on Chumash, Shemos-Yisro

Rashi to Pasuk 3:12 ד״ה וַיֹּאמֶר כִּי אֶהְיֶה עִמָּךְ —

And He Said, “For I Shall Be With You…”

Rashi explains that Hashem ensured Moshe that the Jewish people deserved to be taken out of Egypt because they would later accept the Torah on Mount Sinai.

INSIGHT: Future Merit

In his commentary to Bereishis (21:17), Rashi explains that Hashem only judges a person based on his current behavior— not his future actions. Therefore, Hashem provided water for Yishmael in the desert, without considering the sins that he or his offspring would commit in the future. Similarly, the Midrash (Shemos Rabbah 3:2) teaches that Hashem redeemed the Jewish people from Egypt, despite the Sin of the Golden Calf, which He knew they would later commit, for He sees iniquity but does not consider it (Iyov 11:11), instead limiting His judgment to the present moment. However, Rashi’s comment to our verse indicates that Hashem does account for the future in judgement, for He credited the Jewish people with the merit of accepting the Torah before they had done so!

To resolve this contradiction, Parashas Derachim suggests that although Hashem does not account for our future transgressions, He does account for our future merits, for His system of justice is tempered by His great mercy and kindness. Indeed, while those very people who would later accept the Torah would also participate in the Sin of the Golden Calf, Hashem redeemed them for their future merit while simultaneously ignoring their future iniquity (Parashas Derachim §4; see Zohar, Vol. 1, 121b).

Rashi to Pasuk 5:20 ד״ה וַיִּפְגְּעוּ —

They Encountered.

Rashi explains in his second approach that the “the officers of the Children of Israel” who spoke harshly to Moshe and Aharon were the wicked Dassan and Aviram (Nedarim 64b; Shemos Rabbah 5:20).

INSIGHT: Dassan and Aviram’s Conflicting Traits

While Dassan and Aviram are noted throughout the Torah for their wickedness (see Rashi above, 2:13, 15, 4:19; below, 16:20; Bamidbar 16:1, 12-14, 27), according to this approach of Rashi, they possessed an element of great virtue: They were among the officers of the Children of Israel who let themselves be beaten rather than enforce Pharaoh’s unfair work quota on their brethren! Now, Rashi explained in v. 14 that the officers who took such beatings merited to become members of the Sanhedrin and attained prophecy. This does not mean that all the officers achieved that status. There were thousands of officers (one for every ten Jewish laborers; Shemos Rabbah 1:28), and only seventy of them — the most worthy ones from each tribe — were appointed to the Sanhedrin. Dassan and Aviram surely were not on the Sanhedrin. However, the merit of taking beatings for their brethren benefited them in another way. Rashi writes below (10:22) that there were wicked Jews who did not want to leave Egypt and they died during the Plague of Darkness. Dassan and Aviram were in that evil group, but they survived, and in fact remained in Egypt when Moshe led the Jews out at the time of the Exodus (Targum Yonasan to 14:3 below). At some later time, they joined the Jews in the Wilderness and resumed their wicked behavior. Why did they not die during the Plague of Darkness? R’ Yehoshua Leib Diskin explains that it was in the merit of the beatings that they took on behalf of their brethren. Despite their evil desire to remain in Egypt, they were spared from death. But while they gave of themselves for their brethren, their behavior toward Hashem remained evil, and when the Jews left Egypt they chose to remain behind. After the Splitting of the Sea, when all the Egyptians drowned and it was evident that Egypt had no future, Dassan and Aviram joined the other Jews in the Wilderness. There they carried on their wicked ways, acting as thorns in Moshe’s side until they were swallowed up by the earth together with Korach (Maharil Diskin al HaTorah).

R’ Chaim Kanievsky would often point out a lesson to be learned from this incident. One who suffers on behalf of his fellow Jews gains enormous merit which may save him from death even if he has grave sins — but there is a limit to this merit. Once the person gets involved in dispute, as Dassan and Aviram did when they joined Korach’s rebellion, even the great merit of taking blows for other Jews will not save him (Minchas Todah [Honigsberg], p. 443).