Adapted from: Rav Yaakov Bender on Chumash 2

וַיָּבֹאוּ בְנֵי גָד וּבְנֵי רְאוּבֵן. . . עֲטָרוֹת וְדִיבֹן וְיַעְזֵר וְנִמְרָה וְחֶשְׁבּוֹן וְאֶלְעָלֵה וּשְׂבָם וּנְבוֹ וּבְעֹן.

The children of Gad and the children of Reuven came… Ataros, and Divon, and Yazer, and Nimrah, and Cheshbon, and Elalei, and Sevam, and Nevo, and Beon (Bamidbar 32:2-3).

In listing the lands in Eiver HaYarden, the areas chosen by the Bnei Gad, Bnei Reuven, and half of Shevet Menasheh, the Targum Onkelos provides details on the towns listed.

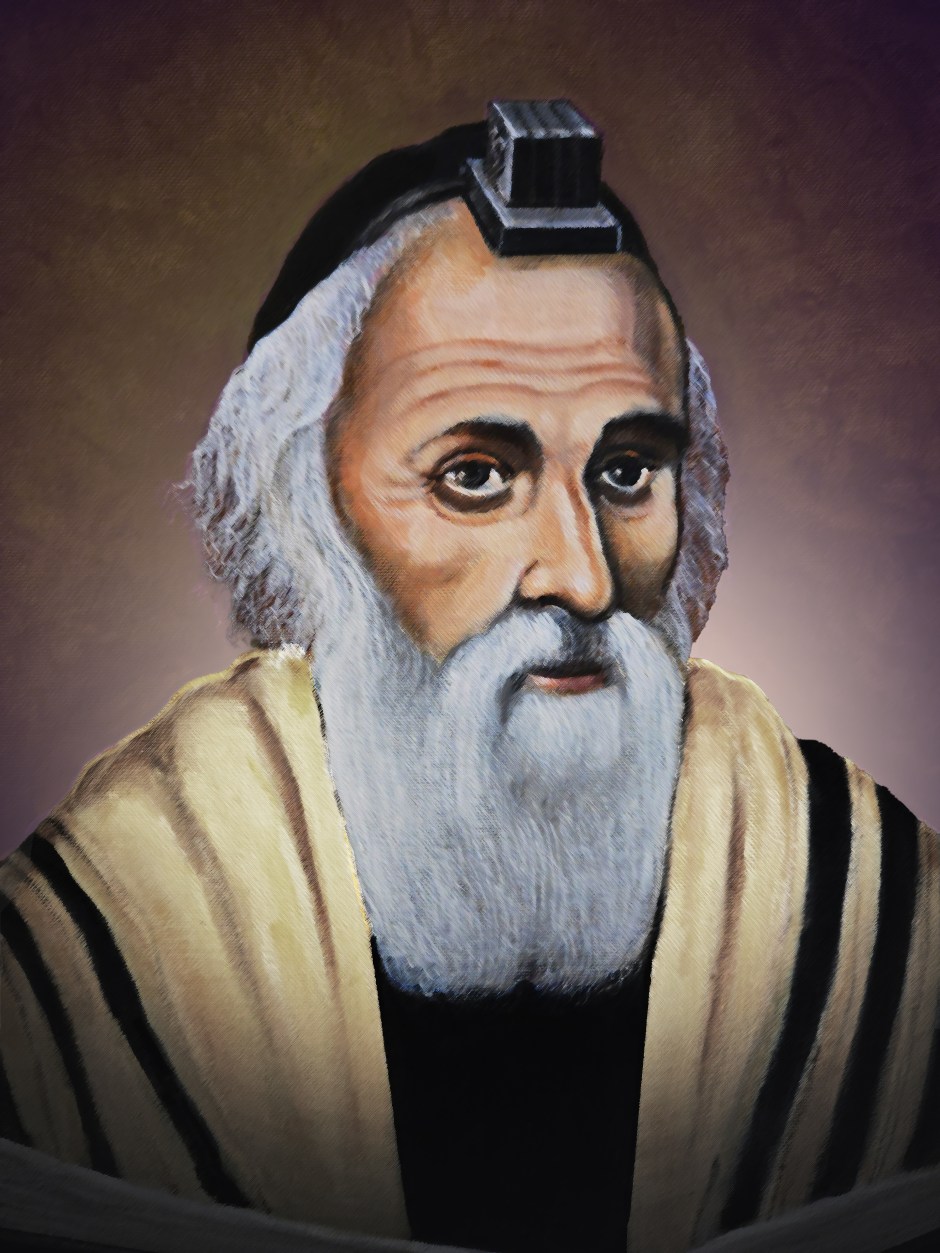

Cheshbon, he says, was Beis Chushbena, a place inhabited by those who made calculations, while the town of Elalei was Baal Devava, a place of fighters. Nevo, Targum says, was beis kvurta d’Moshe, the kever of Moshe.

The fact that it was Moshe Rabbeinu’s resting place is important, but identifying the town this way and this way only would seem to be in marked contrast to the other places, in which the Targum either translated the words, such as Ataros as Machlelta, or tells us a detail about the people who lived there. Moshe Rabbeinu’s burial place, however, was a feature that would eventually mark the place, but it did not the define the town and it had not yet happened. Why does Onkelos switch his description of this one place?

The Chofetz Chaim famously commented that the largest cities on the map, Warsaw, Krakow, Vilna, Moscow, or St. Petersburg, had stars near their names, their letter bolded so that travelers could easily identify them. Smaller towns appeared on the map, but without any star. The smallest towns did not even appear on the map with anything more than a tiny dot.

“But even if Radin has no star on the government-issued map,” he said, “in Shamayim, there is a big star on the map near Radin, because we have a yeshivah where bachurim learn Torah.”

R’ Yitzchak Hutner told a story about a Yid who came to Vilna for the first time. He hired a coachman to drive him, and he sat in the carriage, learning from his Gemara.

The wagon driver turned to ask him what he was learning. The passenger, assuming the driver to be unlearned, gave a polite, curt answer.

The wagon driver was intimately familiar with the topic, and he engaged the passenger in a conversation on the sugya. The passenger was impressed and shared a question of his own. The driver had an answer, and a learned discussion ensued.

Finally, the passenger could not contain his curiosity, and he asked the question on his mind.

“In any town, you would be the rav. How is it that in Vilna you drive a wagon?”

The coachman explained that Vilna was a town filled with great talmidei chachamim and he was not unique just because he knew how to learn. This, he explained, was because of the Vilna Gaon.

“Is he the rav of the city?” asked the passenger.

“No,” said the wagon driver, “he is not the rav.”

“Is he the maggid meisharim?”

“No,” came the reply.

“Is he the rosh yeshivah?” the passenger persisted.

“He was none of those things, and he is not even alive. He was niftar over a hundred years ago,” said the driver.

“So how did he make you a talmid chacham?” asked the scholarly passenger.

“Veil ehr iz duh gevehn! Because he was here!” said the driver emphatically.

There are features in the history of a town that are so monumental, so immense, that they mark the town forever and the place lives on, forever bound up with that event or personality. Vilna will forever be associated with the man who learned Torah in a room with the shutters drawn. It is his city, and no other detail means as much to a Torah Jew.