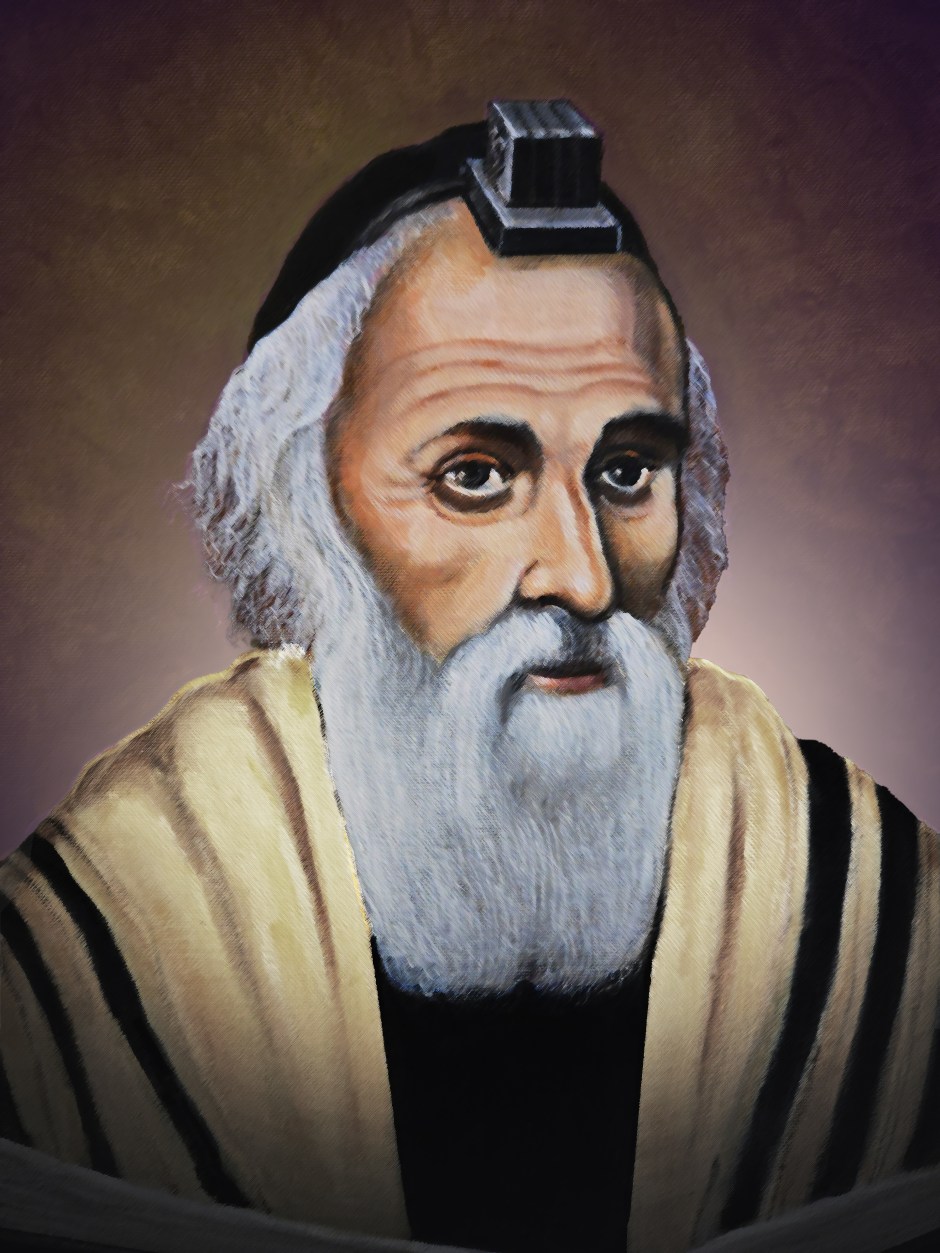

Adapted from: Live the Blessing – Chofetz Chaim Heritage Foundation

Obviously, if everyone could hear all our thoughts, the average person with the average level of tolerance would be leaving emotional casualties all over the highways and byways of his life. We don’t want people to know everything we think, because sometimes those thoughts will discourage or hurt them. They don’t need to know that we think their business idea will never amount to anything, or that their new spouse seems a bit odd, or that we find their conversation boring. Many such thoughts are just fleeting impressions, but if we focus on them or voice them, they change our reality.

Negativity can sour relationships even when it’s not personal. Nobody enjoys the company of the person who always finds the downside of every situation and complains about it. The food isn’t hot enough, the band is too loud, the speaker goes on too long, the teacher is too strict, the room is too cold; people who share these thoughts regularly seem to be forbidding those in their circle to have a moment of unadulterated enjoyment.

Many people have trouble recognizing where to draw the line between what they think and what they say. While the best of all possible solutions is to see and think only good, this is a level that may take a lifetime to reach. In the interim, a person who wishes to sow goodwill and live in peace with others has to learn the fine art of leaving certain negative thoughts unsaid.

What are those thoughts? They’re the ones that say, “I don’t trust your judgment,” or “He always has to do everything his way,” when a person is doing things differently than we would. They’re the thoughts that cast a shadow over another person’s joy or call into question a decision that he has finalized. In the vast majority of situations, negative thoughts should remain just where they were born – inside our own head.

Peaceful, positive relationships can’t compete against the constant din of negativity. Hashem taught us this when He brought us out of Egypt. The splendor of that moment would have been thrilling enough for the Jews who followed Moshe out of slavery; but to make our joy complete, Hashem restrained the dogs of Egypt from barking as we left. We learn from this that when the only result of our noise will be to vex another person, silence is a far better option.

Menachem and Dave, old classmates, started out together in new jobs at the same company. They worked in two different departments, but both took their lunch from 1 to 1:30 in the small company dining room. Each was happy to see a familiar face, and they began eating together every day.

Over the course of a few days, they caught up with each other’s lives. Then they began talking about the jobs they now held and the company they worked for. “Baruch Hashem, this job came up at exactly the right time,” Dave said. “I had really outgrown my other position and was looking for a challenge, not to mention a raise. There’s lots to learn here.”

“Sure, but I wish they’d get their act together,” Menachem commented. “I don’t know about your work in the IT department, but let me tell you that in sales, no one’s got a plan. You’re really on your own, learning the job.”

“Well, that’s part of the challenge,” Dave said.

“I don’t buy it. They just don’t want to invest in training,” Menachem answered. “If I want to know anything, I have to track someone down who’ll give me a minute of his time, and if I need more than that, I’m sunk.”

Now Dave began pondering his own “learning curve” and thinking about the distracted, incomplete answers he was getting to his own questions. Maybe Menachem was right. The company wasn’t well run. “Maybe I should have taken a different offer,” he thought, feeling just a bit deflated.

Before voicing your negativity about something, ask yourself if your words are likely to sour the other person’s mood or outlook [or if they are loshon hora]. If so, try to find the positive, or simply leave your comment unspoken.