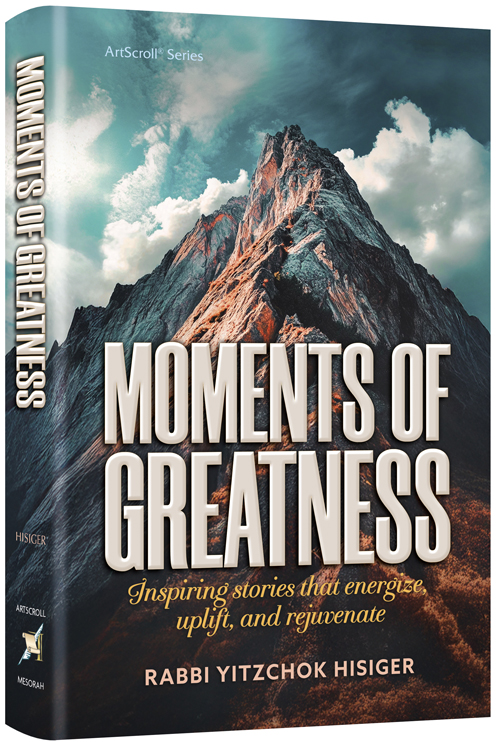

Adapted from: Moments of Greatness by Rabbi Yitzchok Hisiger

It was after the chuppah at his daughter’s wedding and R’ Moshe Goldberg, maggid shiur at Yeshivah Gedolah Zichron Shmayahu in Toronto, sat down to eat something before family pictures were taken.

Joining him was his younger brother, R’ Yehudah Goldberg, maggid shiur at Yeshivah of Telshe Alumni of Riverdale. Immediately, R’ Moshe turned to him and began discussing a Rashba found in the sugya of keren telushah (Bava Kamma 2b) that he was learning in yeshivah. R’ Moshe, with unbridled excitement and exhilaration, discussed the words of the Rashba relating to the topic of whether negichah, the goring of an ox, refers to an animal attacking with an attached horn or to an animal striking with a detached horn that it holds between its teeth.

Oblivious to the wedding festivities around him, R’ Moshe was fully engaged in his Torah discussion, no different than if he were in a beis midrash surrounded by yeshivah bachurim.

When R’ Moshe concluded the vort, his brother gave him a hug and a kiss.

“R’ Moshe,” exclaimed R’ Yehudah. “Biz ah hundred un tzvontzig (until 120 years), I will never forget that in the middle of your own daughter’s chasunah, you told me a Rashba on keren telushah!”

R’ Moshe turned to his brother, wishing to correct him.

“In mitten mein tochter’s chasunah? In middle of my daughter’s wedding we discussed keren telushah? Nein! No! That is incorrect. Rather, in the middle of the Rashba on keren telushah we celebrated my daughter’s wedding!”

R’ Moshe wasn’t just being “cute.” In fact, he truly meant — and lived — what he said. His life was one of Torah. Everything else revolved around Torah. R’ Moshe understood what is the ikar and what is the tafel. He understood what is primary and what is secondary.

And this is a lesson for all of us.

Are we consumed with our avodas Hashem and find the necessary time to tend to our personal needs in the middle of our continuous service to our Creator, or are we always in the middle of everything else and just manage to squeeze in some obligatory time for Hashem amid our preoccupation with life?

So, what are we consumed with and what is our diversion?

Are we squeezing our spirituality into our day-to-day goings-on or do we squeeze our daily obligations into a life devoted to spirituality and chessed?

The question is: At any given time, what are we in the middle of; what is our priority?

For R’ Goldberg, the Rashba on keren telushah was his preoccupation. Everything else, even his daughter’s wedding, fit in around what to him was life itself: Torah.