Adapted from: What if on Yamim Tovim 2 Adapted by Rabbi Moshe Sherrow from the works of Rabbi Yitzchok Zilberstein

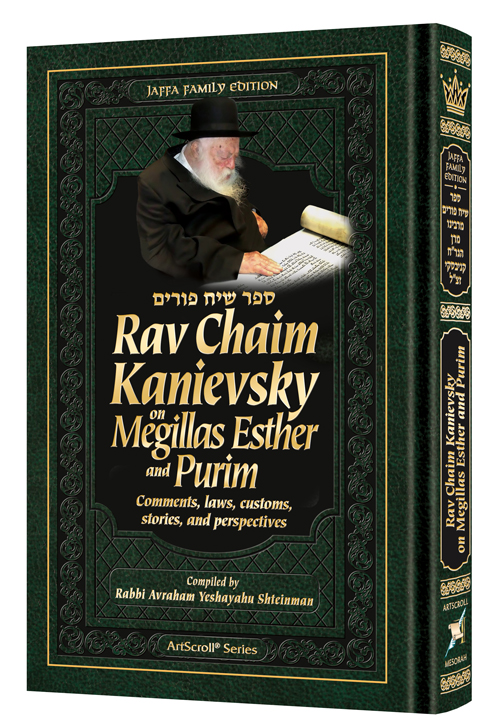

Q: One Purim, around one hundred years ago, many Yidden who were residents of the city of Saana in Yemen brought mishloach manos to Rabbi Shlomo Alkara, their beloved rav. One poor Jew also wanted to bring mishloach manos to the rav, but he had nothing in his home to offer. The only food he found was a rotten radish. He wrapped it in a pretty napkin, put it on a plate, and waited on line to give it to the rav.

When he presented his offering to the rav, the rav’s face lit up and he blessed the man warmly. When the next man in line gave the rav his mishloach manos, the rav blessed him and in return gave him as mishloach manos the package he had received from the poor man. When the man unwrapped the napkin to examine its contents, he discovered the rotten radish.

The rav spoke immediately. “Do you think that the man wanted to insult me? Chalilah v’Chas. This was the offering of a poor man who had nothing else to give. Such an offering is exceptionally precious. On this the pasuk states, v’nefesh ki sakriv korban minchah la’Hashem, When a man among you brings an offering to Hashem; he brings his nefesh (soul) with the offering. And now, if you are zealous for my honor, fill this man’s house with bounty so he will have the means to give an honorable mishloach manos.”

Everyone sent the poor man mishloach manos as per the rav’s instruction, until he was inundated with food. In this way, the townsmen fulfilled the mitzvah of mishloach manos as well as the mitzvah of matanos l’evyonim.

Could the poor man have fulfilled the mitzvah by proffering a rotten radish, had there been another food accompanying it, or, since a rotten radish is inedible, was it eligible to use for the mitzvah?

A: The Chasam Sofer explains that there are two reasons given for the mitzvah of mishloach manos. The Terumas HaDeshen maintains that it is in order to ensure that people will have the wherewithal with which to make a seudas Purim. Even if the recipient has more than enough food for his Purim feast, one has nevertheless fulfilled the mitzvah. In that way, even those who do not have enough will not be embarrassed to accept for themselves, since all Jews send each other gifts of food without discrimination. The Manos HaLevi taught that the rationale behind the mitzvah of mishloach manos is to create peace and love between Jews. This is to contradict Haman’s accusation that the Jews are dispersed and separated by machlokes (strife). Thus, we have a mitzvah to effect the exact opposite.

It would seem that a rotten radish could not be used for the seudas Purim, nor would it engender peace and friendship, so according to both reasons, it could not satisfy the requirement of mishloach manos. It must be that the radish was not completely rotten, and although a more discriminating diner might not have eaten it, most people would.

The poor man recognized the rav’s great stature, including the fact that the rav sufficed with simple fare, as the mishnah teaches us in Pirkei Avos, kach hi darkah shel Torah; pas b’melach tocheil… This is the way of Torah: Eat bread with salt ….” The rav would certainly have been satisfied to accept such a radish; hence, the man would have fulfilled the mitzvah of mishloach manos had he given another food item with it.