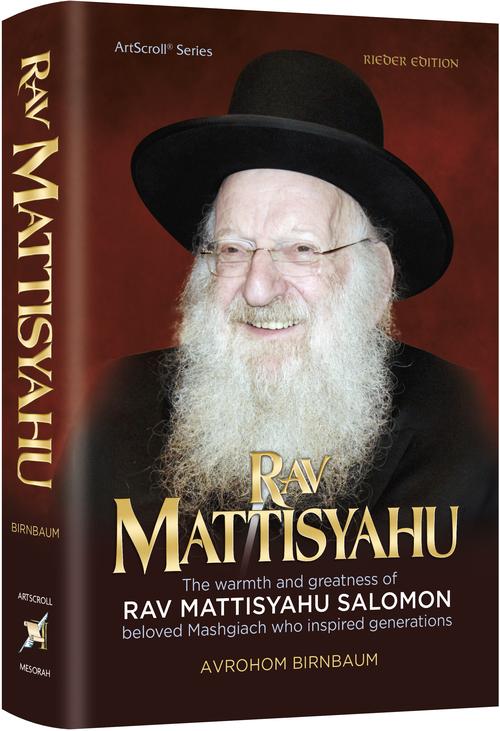

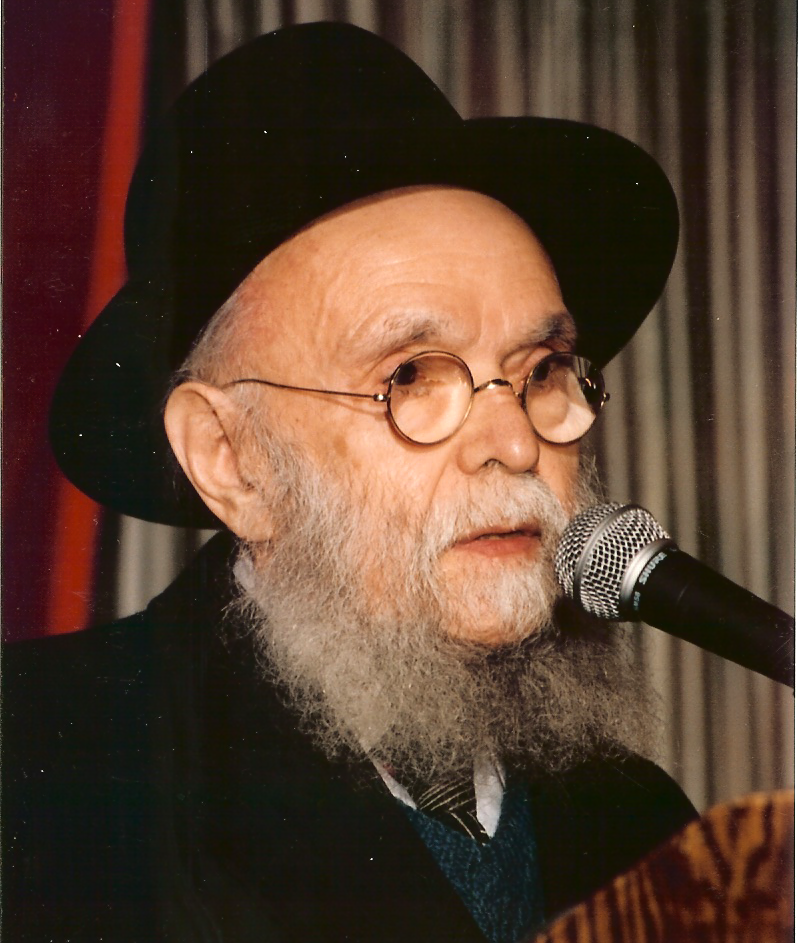

Adapted from: Rav Mattisyahu by Avrohom Birnbaum

It was more than thirty-five years ago. I was a young bachur learning in Gateshead when my father took ill. The Mashgiach, Rav Mattisyahu Salomon, understood the situation and called me into his room to schmooze. He asked me if I was aware of the seriousness of my father’s condition. I answered in the affirmative. From that moment on, he slowly and sensitively began to prepare me for the days, weeks, and months ahead.

A short time later, my father passed away.

I was devastated, but I had already been somewhat prepared by the Mashgiach on how to cope with the new situation. The Mashgiach did not come to the shivah, but the very next day, the day after the shivah, there was a knock on the door. Standing there was Rav Mattisyahu, who had made the five-hour trip from Gateshead to London just to visit us.

He came in and sat with my mother, my brother, my sister, and me, giving us chizuk, comforting us, and preparing us for the difficult road ahead.

Time passed. Before long, the first Yom Tov after my father’s passing was approaching. It was a few days before Shavuos when I asked Rav Mattisyahu permission to go home for Yom Tov.

Surprised by my request, he gently prodded, “You don’t plan on being in yeshivah for the day of kabbalas haTorah?”

“My mother is alone,” I explained. “I can’t leave my mother alone for Shavuos!”

The Mashgiach offered what seemed to be a simple eitzah. “So let your mother come here for Yom Tov.”

“But my mother doesn’t know anyone in Gateshead.”

“That’s not a problem” was Rav Mattisyahu’s rejoinder. “She should come to us! We would love to have her as our guest for Yom Tov!”

A day or two later, the phone rang in our home in London. It was Rebbetzin Salomon calling. After making small talk, the Rebbetzin warmly and enthusiastically invited my mother to come to Gateshead for Yom Tov. The invitation was given with such heartwarming sincerity that my mother couldn’t turn it down.

She arrived in Gateshead before Shavuos, and despite the differences in backgrounds, she instantly felt an extremely close connection with the Rebbetzin, and they became friends. The Mashgiach invited me, my brother, and my sister, who was in Gateshead Sem, to eat all the Yom Tov seudos together with them. It was a memorable, wonderful Yom Tov.

Barely three months later, the phone again rang in my mother’s home in London. It was the Rebbetzin this time, inviting her to come for Rosh Hashanah. My mother accepted the invitation, came for Rosh Hashanah, and davened in the yeshivah. As a result, I also ate the Rosh Hashanah seudos at the home of the Mashgiach.

I was a talmid in the Gateshead Yeshivah for the next four years. Every Yom Tov during those four years, my mother came as a valued guest of the Salomons. But her Yom Tov visits did not end after my four years there. No! The Salomons continued to invite her, and she returned to Gateshead for Yom Tov even after I had left.

The Mashgiach made a personal chavrusashaft with me, and our connection continued for many years.

In truth, our connection transcended the typical mashgiach-talmid relationship. Rather, the Mashgiach served as a father figure who took our entire family under his wing.