Adapted from: The Master of Mercy…and Me by Rabbi Yechiel Spero

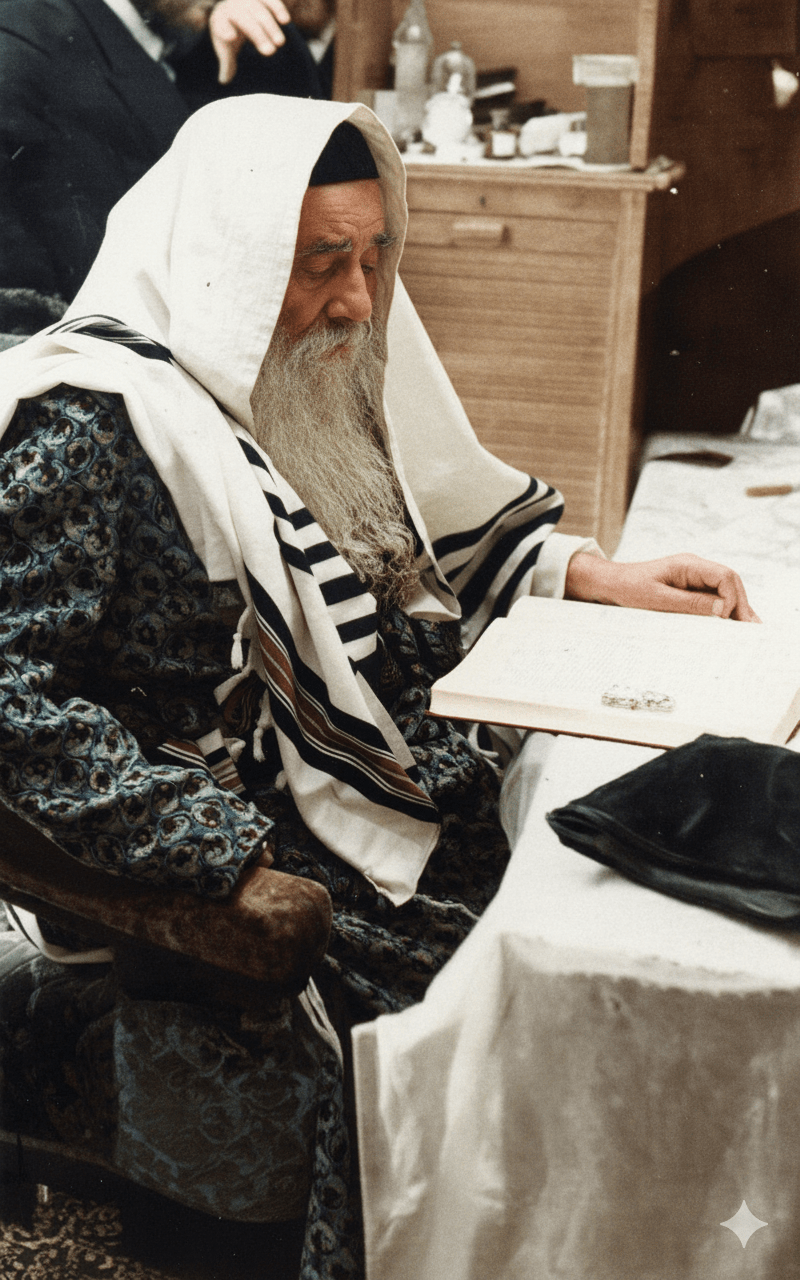

אֵ־ל מֶלֶךְ יוֹשֵׁב עַל כִּסֵּא רַחֲמִים

G-d, King Who sits on the Throne of Mercy.

This introductory tefillah, which leads into the Yud Gimmel Middos, comes from the siddur of R’ Amram Gaon. Like Keil Erech Apayim, it sets the stage for everything that follows.

Keil — This Name conveys two powerful truths. First, as a Melech, Hashem is the Baal HaKoach; there is nothing beyond His power — nothing we can conceive, and even that which we can’t begin to imagine. But Keil also reflects His nature of pure Kindness. As Tomer Devorah (a most significant sefer on the Yud Gimmel Middos shel Rachamim) explains, He is a King of inexhaustible Chessed. His goodness extends to the farthest corners of the universe, touching even those who feel distant from Him.

Yosheiv — He sits. Shelah HaKadosh explains that this word tells us that Hashem is always ready. Always waiting. Always poised to hear the cries of His people. Always prepared to turn toward us the moment we turn toward Him.

Al Kisei Rachamim — He sits on the Throne of Mercy. Ready to take Din, strict Judgment, and transfer it to a place of Compassion. He doesn’t sit in Judgment with harshness. He sits with a desire to forgive, to heal, to draw close.

This is how we begin.

With a Father Who conveys power and Kindness; Who is there for us; Who is ready to forgive us when we repent.

A Story: Why Didn’t I?

Before the skies over Europe darkened with smoke and screams, there was a flicker of hope. A miracle called the Kindertransport. Ten thousand Jewish children, plucked from the jaws of Nazi Germany and Austria, were brought to safety in England. Away from danger, away from the gas that would fill the air soon after.

Years later, the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) invited one of those survivors — a man now in his eighties — to share his story on the radio. He was twelve at the time of the transport. And though many years had passed, there was one moment, one memory that never left him.

When the children were first brought to England, they cried, clinging to memories of home and the arms of their mothers, now thousands of miles away.

Some of them adjusted. Some even smiled again.

But there was one boy who refused.

It made no difference what they gave him — candy, toys, comfort — he never stopped crying. His pain could not be soothed. Finally, the caretakers asked him, “What do you want?”

“I want to speak to the king,” the boy answered confidently.

“The king of England?”

“Yes, I want a private meeting with him.”

Instead of dismissing him, the caretakers acquiesced. “All right, but if you’re going to meet the king, you must prepare. There is a way to walk. A way to speak. A way to behave before royalty.”

For three weeks, the little boy practiced. He studied. He learned. And he believed.

King George VI had recently begun his reign. An unlikely king — born with a stutter, never meant for the throne — was now charged with holding together a nation at war. Still, in those first months, the king made it his mission to visit the people of his kingdom.

The big day arrived. The boy was brought to the city square, where crowds waited behind barricades to catch a glimpse of the king’s carriage. But as the crowd grew, the boy realized: He would not have a private meeting. He was just going to wave.

No. That wasn’t enough. So, as the royal carriage passed, he jumped the barricade.

He ran with all his might, a twelve-year-old boy with tears in his eyes and hope in his heart. But the royal guards tackled him to the ground and placed him in handcuffs.

The crowd gasped in surprise. So did the king. Peering out of the carriage, King George saw the boy and ordered, “Let him go.” He motioned to bring the boy into the carriage.

The boy stood up, shaken, his eyes wide. “Why did you run to me?” the king asked.

At first, the boy couldn’t answer. But then, through his thick accent and halting English, he said, “I was brought to England. I left my parents behind. I miss them. I need them.”

The king, himself a man who had once struggled to speak, understood.

“And what do you want from me?” asked the king.

“You’re the king of England,” the boy said. “Please… bring my parents to me.”

“We’re at war with Germany. That’s not something I can just do.”

“But you’re the king! You can do anything!”

The king’s eyes softened. “Don’t cry,” he said. “I promise I will try. I will do everything I can. Just… don’t cry.”

Two days later, a knock was heard at the orphanage door.

It was the boy’s parents.

Somehow, they had been brought out of Germany. Reunited with their son. Saved.

Back in the radio studio, decades later, the survivor finished telling his story. Then the tears came rushing back. “I will never forgive myself,” he admitted.

The host was puzzled. “Why? You were the one who asked. You were the one who was saved.”

“No,” the man said. “You don’t understand. It wasn’t me. I wasn’t the one who jumped the barricade. That boy, that hero, that child of courage — it wasn’t me. I was there. I watched. I stood frozen. And I will never forgive myself.

“Why didn’t I?”

As we prepare for the Days of Awe, we must know that the King is in the field. He is walking among us. Accessible. Listening.

And we, too, are standing behind the barricade — unsure, timid, hesitant.

But what if we were to jump?

What if we were to dare cry out with sincerity, “Ribbono shel Olam — I need You! I miss You! I want to be close to You again!”

What if we were to dare ask for the seemingly impossible?

What if we were to believe, really believe, that the King can do anything?

○ TAKEAWAY ○

Don’t let the moment pass. Don’t look back and ask yourself, “Why didn’t I?”

Jump the barricade. Now is the time.