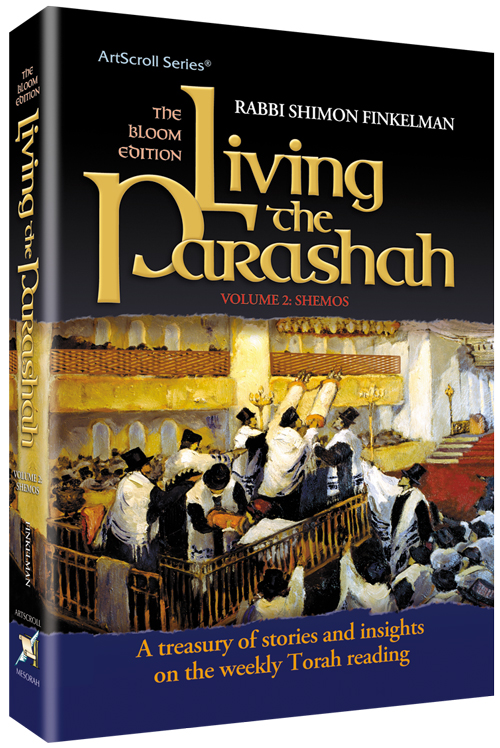

Adapted from: Living the Parashah by Rabbi Shimon Finkelman

וַיֹּאמֶר ה’ אֶל מֹשֶׁה, אֱמֹר אֶל אַהֲרֹן: קַח אֶת מַטְךָ וּנְטֵה אֶת יָדְךָ עַל מֵימֵי מִצְרַיִם …

Hashem said to Moshe, “Say to Aharon: ‘Take your staff and stretch out your hand over the waters of Egypt … ’ ” (Shemos 7:19).

“Say to Aharon” — Because the river protected Moshe when he was cast into it, therefore it was not stricken through his hand, neither with the plague of blood, nor with the plague of frogs; rather, it was stricken through the hand of Aharon (Rashi from Shemos Rabbah 9:10).

Later in this parashah, Rashi informs us that when the time for the plague of lice came, the soil could not be stricken through Moshe, for he had benefitted from it as well. As inanimate objects, the Nile and the soil of Egypt did not willingly assist Moshe and would not have been “offended” had he brought plagues upon them. Nevertheless, explains Rabbi Eliyahu Dessler, when a person damages something that he benefited from, this has a detrimental effect on his personality and will corrupt his own midah of hakaras hatov, gratitude.

Torah personalities have always excelled in their hakaras hatov towards those from whom they benefitted. This was certainly the case with Rabbi Sholom Eisen, one of Jerusalem’s foremost poskim.

During his final illness, R’ Sholom was attended to by yeshivah bachurim, who cared for him with true devotion. Despite the pain and other difficulties R’ Sholom strained himself to travel great distances in order to attend the weddings of these bachurim and would deliver an address in honor of the occasion.

When his illness worsened, R’ Sholom’s doctors advised that he be brought to America for treatments. The treatments were not successful and R’ Sholom returned to Jerusalem in grave condition.

Taanis Esther arrived and with it came the tragic news that the posek of the generation, Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, had passed away. His funeral was held in New York on Taanis Esther and was to take place in Jerusalem on Shushan Purim, the day on which Jerusalemites perform the mitzvos of the yom tov. A quarter of a million Jews paused in their celebration of Purim to accord final honor to R’ Moshe.

R’ Sholom wanted very badly to participate, but his family insisted that he physically was not up to it. Bedridden and pitifully weak, he accepted their position and remained at home.

Later, he called his son to his bedside and said, “I would like you to gather a minyan, go the grave of R’ Moshe, and ask forgiveness for my not having participated in the funeral.”

“But why, Tatte?” asked his son. “Weren’t you exempt because of weakness?”

R’ Sholom replied, “As far as the obligation to attend the funeral of a gadol hador, I believe that I was exempt. But when I was hospitalized in New York, R’ Moshe, zt”l, visited me. Out of hakaras hatov, I should have attended his funeral — and I do not think that my illness freed me from that obligation.”

Only after his son carried out his wish and, in the presence of a minyan, asked forgiveness at R’ Moshe’s grave, was R’ Sholom Eisen at peace.

Once, Rabbi Elazar Menachem Shach contacted Rabbi Chizkiyah Katzberg, a mashgiach in a Bnei Brak yeshivah and said, “In your yeshivah there is a bachur named Aron Taplin. I would like you to arrange for him to study every day with a kollel member, who will help Aron to advance in his studies. I will pay the young man for this. Please come to me each month on Rosh Chodesh to receive the young man’s payment.”

Rabbi Katzberg wondered why Rav Shach had singled out this bachur for this special arrangement and eventually found out why.

When Rav Shach was a bachur during the First World War, he endured tremendous deprivation. He was all alone, and learned in a beis midrash in Slutzk day and night, living on virtually nothing but bread and water and sleeping on a bench in the beis midrash. He had one shirt, which he washed once a week in honor of Shabbos.

One day, a Jewish woman approached him and said, “I could not help but notice that your shirt is ripped. Shouldn’t you change your shirt?”

“I have no other shirt,” he replied.

The woman soon returned with two shirts for him to keep.

After the Second World War, Rav Shach tried to find out what happened to this woman and her family and learned that her entire family was killed, except for one grandson, Aron Taplin.

Rav Shach’s helping Aron Taplin to advance in his learning was his way of expressing hakaras hatov for what his grandmother did for him.