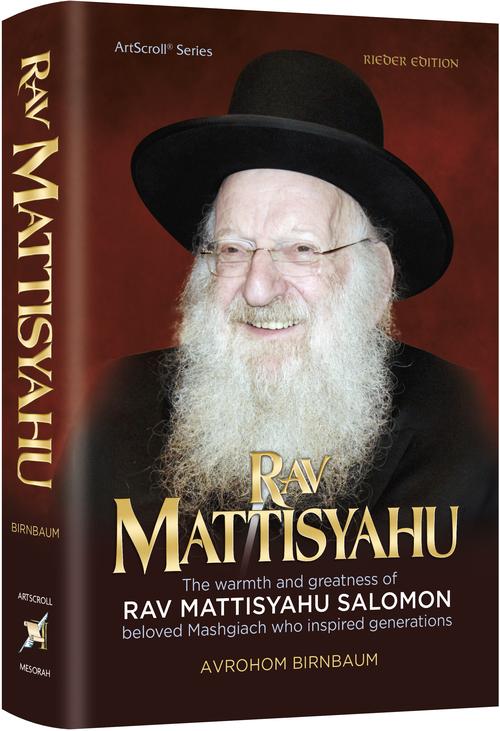

Adapted from: Rav Mattisyahu by Avrohom Birnbaum

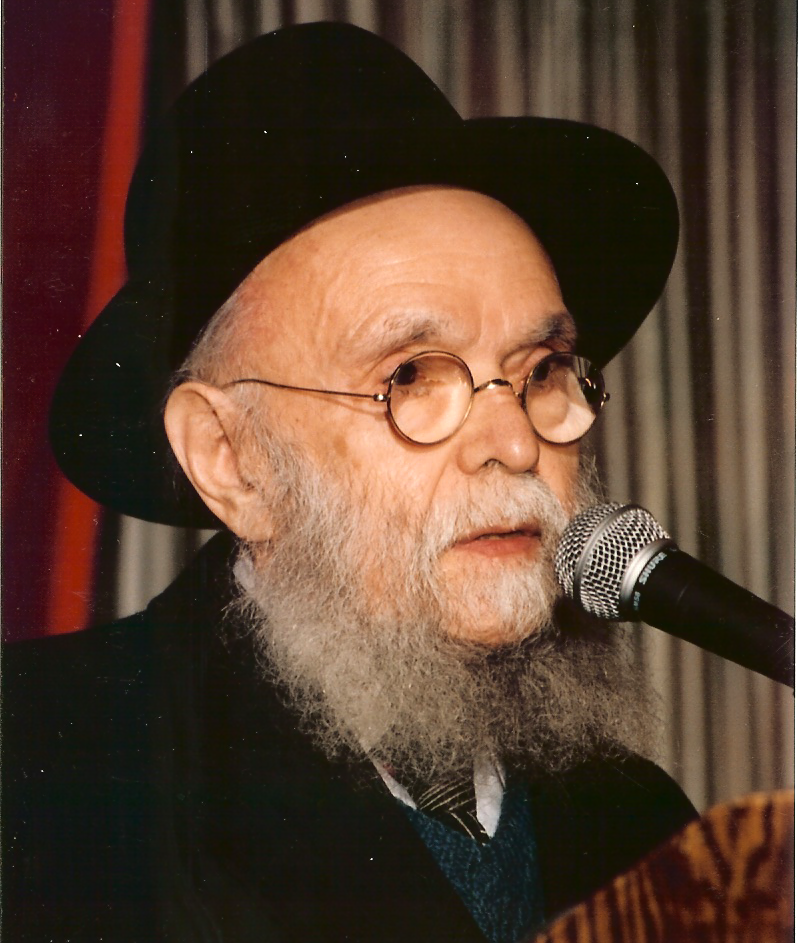

The Mashgiach loved special children. He displayed his love for them openly and enjoyed interacting with them. Whenever he met special children, he would hug and kiss them like a loving grandfather. He understood that they were pure neshamos.

The Mashgiach and the Rebbetzin had a special relationship with Camp HASC, and they looked forward to visiting every year. When they visited, all of the boys would line up in front of the Mashgiach and the girls in front of the Rebbetzin, and each would get personal attention. The Mashgiach also spent time giving chizuk to the staff and the counselors and impressing upon them how much he valued their devotion to Hashem’s special children.

On one of his yearly visits to Camp HASC, he told the children, “I want you to do me a favor. When Mashiach comes, and you are in the front row welcoming him, tell him that I am your friend. It will be a very big help for me!”

Rav Mattisyahu felt it was so important to constantly think about what Hashem does for us and to thank Him. Once, R’ Mordechai Levi walked into the room where the Mashgiach was sitting and asked, “Vos macht der Mashgiach?” How is the Mashgiach doing?

“Hodu laShem ki tov!” was Rav Mattisyahu’s answer.

“Nu,” R’ Levi said cheerfully, “vos ken zein besser?” What could be better than that?

And Rav Mattisyahu replied, “Ki l’olam chasdo!”

Throughout his life, the Mashgiach was cognizant of the chessed that Hashem constantly did with him and was always full of gratitude to Hashem. This sense of deep gratitude and simchah remained with him even in his later years when things were very difficult.

During those years, too, if someone asked him how he was — and everyone knew that he was really not well — he would always answer “Hodu laShem ki tov ki l’olam chasdo!”

The Mashgiach had a very healthy attitude as to how a person should look at life.

R’ Naftali* had been diagnosed with cancer. He decided to seek advice from R’ Shraga Feivel Zimmerman.

“Baruch Hashem,” R’ Naftali told R’ Shraga Feivel, “the cancer is not so virulent and has been caught at an early stage. I have been told that there is a ninety-five percent recovery rate and only a five percent mortality rate.

“My question is this: Should I be worried about dying? In truth, I probably won’t die since there is a ninety-five percent chance that I will survive. Should I ignore the thought of dying? Probably not. After all, there is a one in twenty chance that I’ll die! So what should a Yid think when he receives such a diagnosis?”

R’ Shraga Feivel hadn’t the faintest idea of how to answer, so he called the Mashgiach.

The Mashgiach instantly answered, “If Hashem wanted a person to think he is dying, He would have given him a disease with a fifty-fifty chance. If He gave him a disease with a ninety-five percent chance of recovery, He clearly doesn’t want him to walk around depressed because he is dying.”

“So what should I tell him?”

“Tell the person in my name that he does not fully appreciate the gift of life. Hashem is giving him a wake-up call. Be mechazek him and tell him that he will survive and go on to live a long life, but he should stop taking life for granted.” And he repeated, “He should appreciate the gift of life.”